ISDS in numbers – Impacts of Investment Arbitration Lawsuits Against States in Latin America and the Caribbean

Summary

This report presents a systematic overview of foreign investor lawsuits against countries across Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) based on investment protection treaties up to 31 December 2023.

ISDS in Latin America and the Caribbean

During the 1990s, countries across Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) signed hundreds of international treaties protecting foreign investment and granting investors unprecedented rights, including the right to sue states before international tribunals when they believe their profits had been affected by government actions. These countries expected that signing Bilateral Investment Protection Treaties (BITs) would be decisive in attracting foreign investment. Thirty years on, however, it is evident that BITs did not help in attracting investment, let alone in promoting development. Rather, their effects have been harmful for countries throughout the region.

The negative impacts of BITs are still largely unknown and little discussed either in political and parliamentary circles, or in civil society, academia and social movements. This report highlights the social and financial costs of the investment protection system and international arbitration as a mechanism to resolve disputes between foreign investors and states.

The Explosion in the Number of Claims

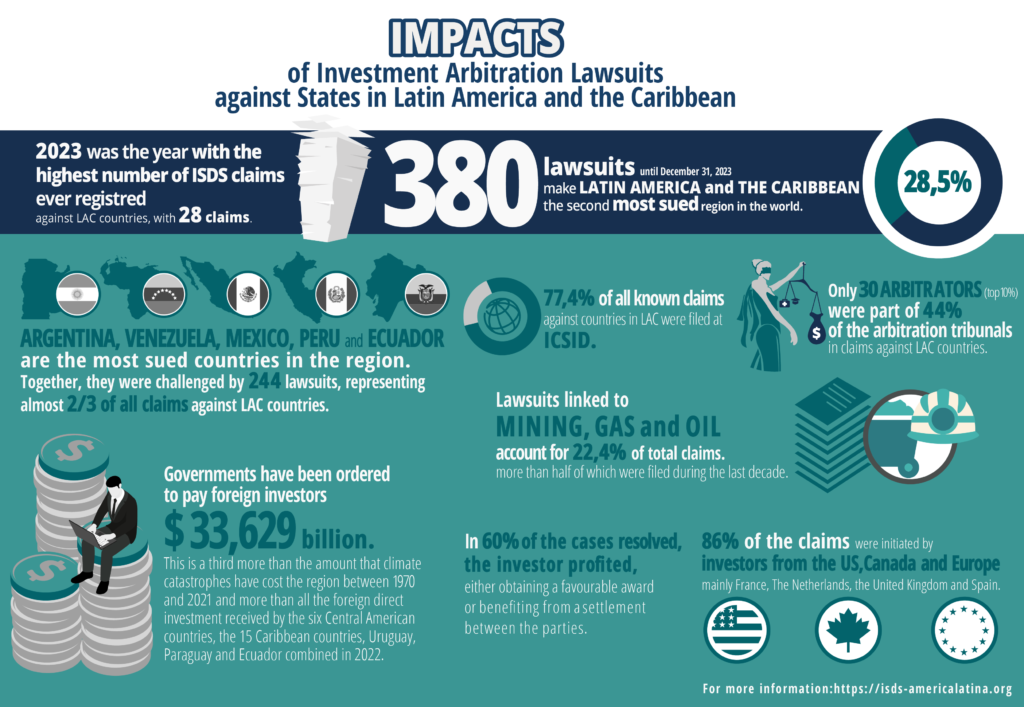

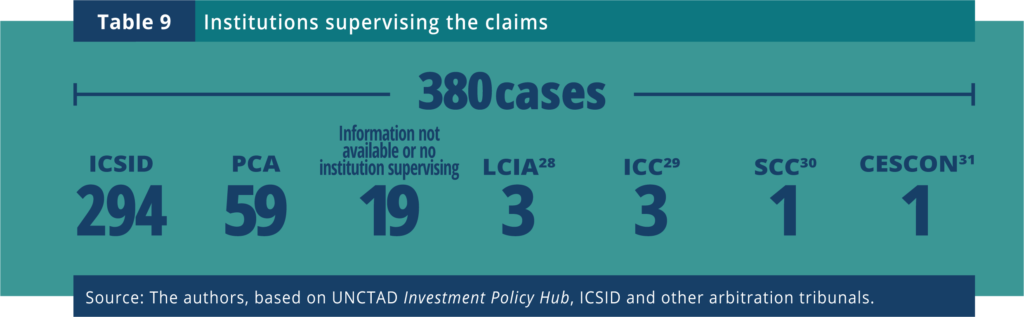

In the last two decades, Investor–State lawsuits have gone from a total of six known treaty-based cases in 1996 to 1,332 at the end of 2023. Countries in South and Central America and the Caribbean were sued on 380 occasions over that period, equivalent to 28.5% of known claims worldwide.

The countries being sued

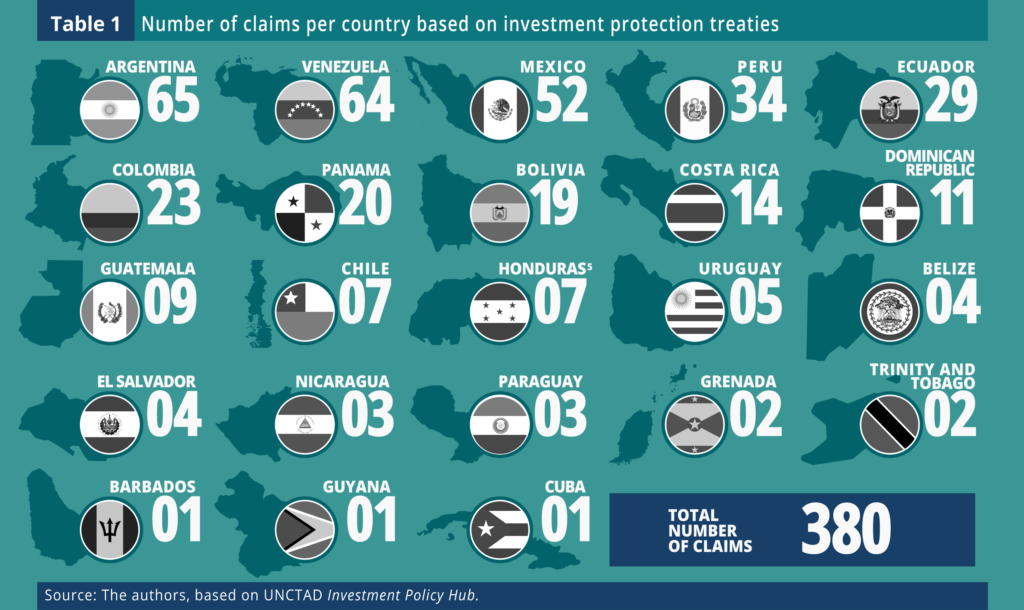

Of the 42 countries in the LAC region, 23 have been sued and brought before the international arbitration system. In order of magnitude, Argentina, Venezuela, Mexico, Peru and Ecuador are the most sued countries in the region. Together, they account for 244 lawsuits, almost two-thirds of all those against LAC countries.

A Boom in Claims Over the Past Decade

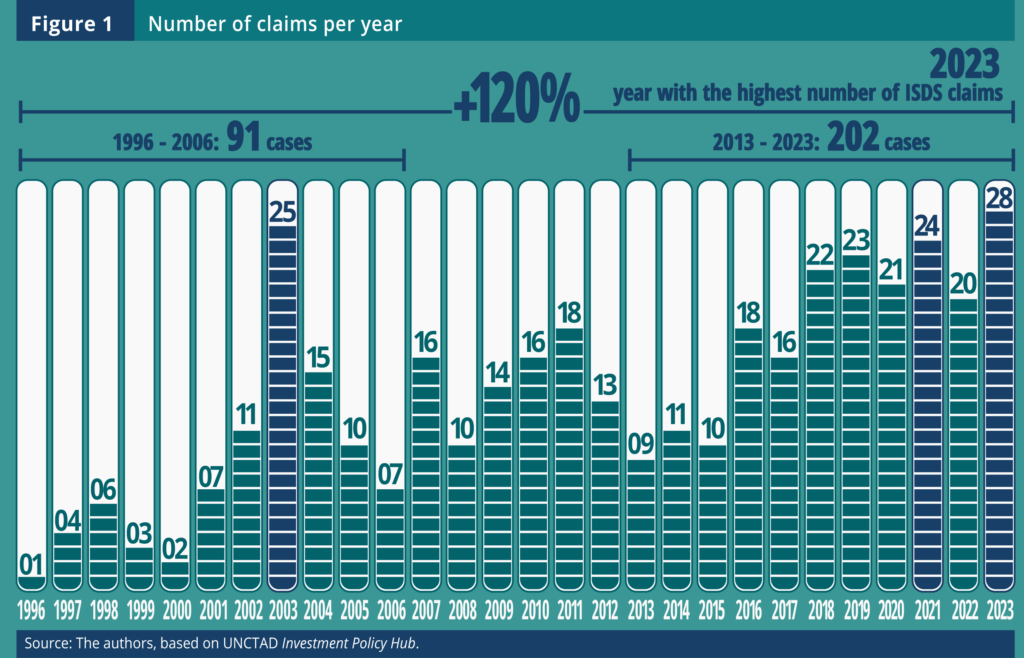

The first claim against a LAC country based on an investment protection treaty was brought against Venezuela in 1996. Since then, the number of lawsuits has been increasing and reached its first peak in 2003, mainly due to the Convertibility crisis, which included a currency devaluation, pesification and freezing of utility tariffs and renegotiation of concession contracts. Of the 25 claims registered in 2003, 20 were against Argentina.

Since then, the number of claims has continued to rise. While 91 lawsuits were registered between 1996 and 2006, in the past decade (2013-2023) these reached 202, a 120% increase over the earlier decade. In fact, 2023 was the year with the most claims in the history of investor-state arbitration in Latin America, with 28 claims registered, of which 11 were from a single country: Mexico. This is because the old investment protection chapter of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) could still be invoked, whose grace period expired in July 2023; three years after its replacement by the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (T-MEC). The T-MEC is a revised version of NAFTA and limits investor-state arbitration between Mexico and the United States to certain sectors, while between the US and Canada and Canada and Mexico it eliminates it altogether.

It is also important to know that there are dozens of threats of ISDS lawsuits and there are many cases in which governments have decided to backtrack on planned measures in order to avoid facing multi-million-dollar lawsuits. An example of this practice, known as regulatory chill, is the threat of the pharmaceutical company Novartis against Colombia for wanting to declare the drug Glivec, which is used to treat blood cancer, as a drug of public interest and strip the pharmaceutical giant Novartis of its monopoly on production, so that generic competition would reduce the price of the drug. Novartis then threatened to sue Colombia in an arbitration court, which is why the Colombian government decided to back down on the measure

Arbitration Winners and Losers

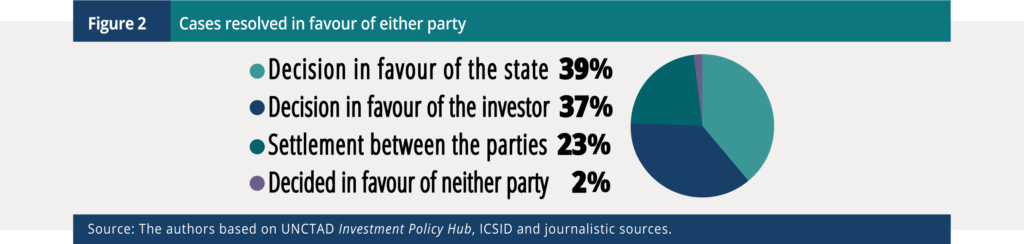

States have been the main losers in investment arbitration cases. Of the 380 known cases against LAC countries, 239 cases were resolved (either by a tribunal award or by an agreement between the parties), 60% of which favoured the investor.

Of the 181 cases where the tribunal issued a ruling (i.e. excluding settlements between the parties), the award favoured the investor in 88 cases (48.6%).

Given that claims incur millions in states’ defence and legal expenses, they always lose out in the international arbitration system. Even when tribunals rule in their favour, they typically hire law firms that may charge an hourly rate of up to $1,000. For example, by 2013 Ecuador had spent $155 million for its defence and arbitration costs. In the Freeport-McMoRan v. Peru lawsuit, the court rejected the US mining company’s claims, but ordered the parties to pay its costs, which in Peru’s case involved almost US$7 million spent on its defence. In addition, when a ruling goes in favour of the investor, the tribunal often orders the state to pay the investor’s arbitration costs. In Perenco’s claim against Ecuador, for instance, the award also ordered the country to pay the investor $23 million to cover its fees.

The Countries that Lost the Most Cases

In terms of the arbitration rulings by country, Argentina stands out. Of the 30 claims where the arbitrators’ decision led to an award, only six favoured the state whereas 23 were in favour of the investor (one decision favoured neither party). In addition to the 18 cases in which a settlement was reached, we can infer that 85% of the claims resolved in the case of Argentina were decided in favour of the investor.

There is also a significant imbalance in favour of the investor in the case of Venezuela, the second most sued country in the region. Of the 35 claims where the decision led to an award, 15 were in favour of the state whereas 20 were in favour of the investor. Adding to these the six cases in which a settlement was reached, we can infer that 63% of the claims resolved against Venezuela were decided in favour of the investor.

The cases against Bolivia and Ecuador show similar outcomes.

The Cost of the Claims

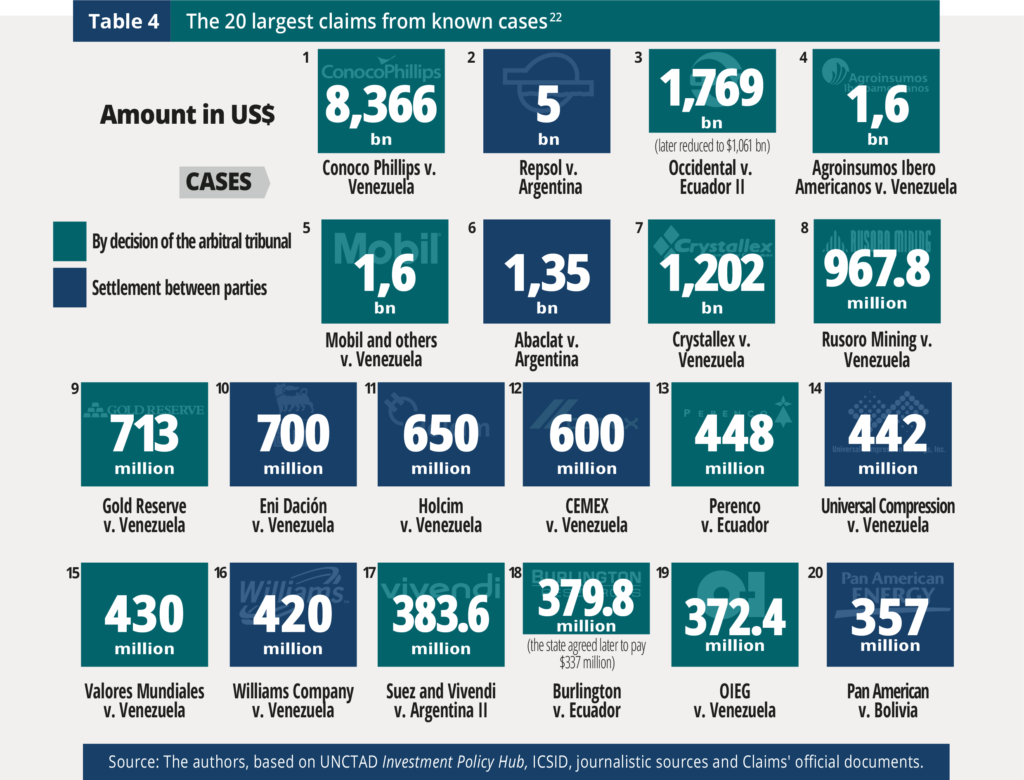

In terms of the amounts, investors’ claims since 1996 total $279,083 bn. In fact, the total claimed is even higher, as in 77 of the 380 claims the amount has not been disclosed.

Based on the disclosed amounts and the cases resolved so far (either by arbitral decision or settlement between the parties), states have been ordered to pay investors $33,629 bn.

In pending claims where the amounts have been disclosed (47 of the 109 claims), investors have claimed a total of $60,674 bn.

The most a country has ever paid as a result of a single claim was $5 bn, which Argentina paid to Repsol after negotiating a settlement with the company.

In absolute terms, the costliest decision was against Venezuela, when it lost the ICSID case filed by Conoco Phillips in 2019. The Tribunal ordered Venezuela to pay an award of $8,366 bn. The country is currently using established procedures to seek annulment of the award.

Investors’ Nationality

The investors that have filed the largest number of claims against LAC countries are based in the United States, with 124 claims, or around 33% of all lawsuits. They are followed by investors from European countries and Canada.

With all the claims brought by US, Canadian and European investors combined, we can infer that they account for 86% of the total.

To a lesser extent, investors based in the region also filed claims against LAC countries. Among these, Chilean investors issued nine such lawsuits, followed by Panama with eight claims. Another interesting case is Barbados, whose investors have filed seven claims, all of them against Venezuela. Only four investor–State lawsuits were filed by companies based in Argentina.

Treaties invoked

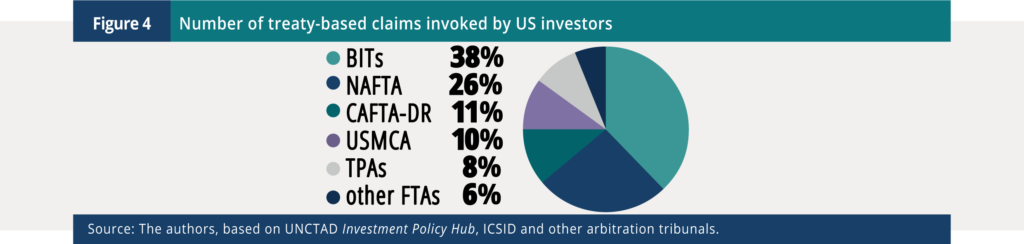

The claims we display in this report are based on treaties signed between countries, whether they are Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) with investment protection chapters or specific investment protection treaties (BITs). In the claims against Latin American countries, investors cited alleged violations of BITs (306 cases) or for contravening FTAs (98 cases). A different treaty format, promoted mainly by the United States and known as Trade Promotion Agreements (TPAs), have already given rise to 12 arbitration claims.

Given that US investors have most frequently initiated lawsuits, it is not surprising that US BITs, along with NAFTA (North-American Free Trade Area), including in its revised version known as USMCA (United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement), and CAFTA-DR (Dominican Republic-Central America FTA), are the most widely used.

It is also interesting to know that a large number of the investors suing Venezuela invoked its BITs with the Netherlands (22 cases) and Spain (17 cases).

Economic sectors affected by claims

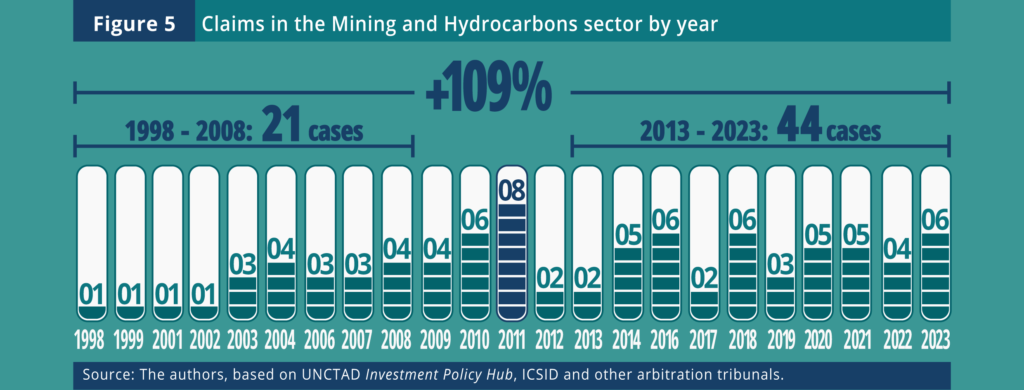

In recent years, most Latin American countries have faced a growing number of claims in the Mining and Oil & Gas sector, where investors have been challenging governments’ environmental conservation policies, regulations protecting the rights of rural communities, and public measures to increase companies’ tax contributions.

Of the 380 known cases against LAC countries, 85 are related to these sectors, or 22.4% of the claims. Comparing the 1998–2008 period against 2013–2023, investors in these extractive sectors sued LAC countries 21 times against 44, an increase of 109%.

The other sectors with a large number of claims are: electricity and gas (53 cases) and manufacturing (48).

Arbitrators in the Cases

The arbitral tribunal is a panel of three arbitrators: one is usually nominated by the investor and one by the state, and the president is appointed by mutual agreement between the parties.

A total of 295 arbitrators have served on tribunals against LAC countries, the vast majority of whom have been involved in only a few cases. Indeed, just 10% of the arbitrators have been elected to sit on 44% of the arbitral panels (where the tribunal is known and/or has been set up).

States tend to prefer certain arbitrators, and have most often appointed the French arbitrator Brigitte Stern. Investors have repeatedly chosen the Argentinian arbitrators, Horacio Grigera Naón and Guido S. Tawil, and the US arbitrator Charles Brower. The Swiss arbitrator Gabrielle Kaufmann-Kohler and Spanish arbitrators Juan Fernández-Armesto, Andrés Rigo Sureda and Albert Jan van den Berg are most frequently appointed as presidents of the tribunal.

The arbitrators’ role on the tribunal depends on the case. For example, one might serve as president of the tribunal in one case and be appointed by the investor in the next. This happened repeatedly with the Chilean Francisco Orrego-Vicuña, who served seven times as president and eight as an arbitrator appointed by the investor; the arbitrators Alexis Mourre and Eduardo Siqueiros have been nominated indistinctly by investors and states.

Regardless of who nominates whom to the tribunal, most arbitrators of the so-called elite are pro-investor lawyers with a background in commercial arbitration.

The Law Firms Defending Investors and States

276 international law firms have been hired by the parties in cases against LAC countries, among which 18 have represented either party in more than 10 cases.

The law firm investors used most often in cases against LAC countries is Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer (59 claims), followed by King & Spalding (34), and White & Case (21). With a few exceptions, states also tend to hire international law firms for their defence, very often Foley Hoag (38 cases) – widely used by Venezuela and Ecuador; Arnold & Porter (32 cases) – supporting mainly Central American and Caribbean countries, especially Panama and the Dominican Republic – and Dechert (24 cases).

The rules of the game and the institutions enforcing them

There are many arbitration centres where investment disputes can be resolved, although most cases worldwide and most claims against LAC are conducted under the auspices of the World Bank’s International Centre for the Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID). Investors used ICSID 294 times for their claims against countries in the region, meaning that 77.4% of all claims were brought to this arbitration centre. Argentina is a case in point, with 61 of 65 claims registered at ICSID.

Some disputes have been addressed in other arbitration centres, for example in the Permanent Court of

Arbitration (PCA) based in The Hague, and in the London Court of International Arbitration (LCIA).

In addition to selecting the arbitration forum, investors have the right to choose the arbitral rules that will govern the case. In the cases against countries in LAC, investors have chosen ICSID rules in 232 of the 380 claims. In addition to the 44 claims submitted under the ICSID complementary mechanism (ICSID AF), ICSID rules were used to resolve disputes in 72.6% of the claims against Latin American countries.

Investors also have resorted to the UNCITRAL rules which belong to the United Nations and have been used in 26.3% of the claims. Investors usually resort to the rules of UNCITRAL and other tribunals when the country is not an ICSID member or has withdrawn from it, as in the case of Bolivia, Ecuador and Venezuela. 13 of the 19 claims against Bolivia and 17 of the 29 against Ecuador were decided under UNCITRAL rules. Since Venezuela withdrew from the ICSID only in 2012, most of the lawsuits it faced before then were dealt with at ICSID and under its rules.